The Loss Of Poland

The invasion of Poland by German forces on 1 September 1939, the action that began the war in Europe, was to have direct and long-lasting consequences for East Lothian. After the collapse of Poland under the weight of a combined attack from Germany and, from 17 September, the Soviet Union, those units of the Polish armed forces that were able to escape, sought exile in France. The fall of France in June 1940 proved a bitter blow to the Poles, who lost their closest ally. However, having pledged to fight on, the Poles left France: by 18 July 1940 almost 17,000 had arrived in Britain. Among them was General Maczek, later to be in command of the 1st Polish Armoured Brigade, who had taken part in an ultimately doomed attack by the 10th Polish Armoured Cavalry Brigade during the German invasion of France.

The Poles Arrive In Scotland

Many of these were to make their way to Scotland and from 1940 to 1942 Poles formed part of the 52nd Infantry Division (HQ Stirling) tasked with the defence of a slice of eastern Scotland that included Fife and Angus. East Lothian, while outside this area of responsibility, was nonetheless home for significant numbers of Polish troops sent here to make use of the superb tank training ground of the Lammermuir Hills. One of the first units to arrive in East Lothian was the 10th Supply Company of the 10th Armoured Brigade, which was based in Ormiston where a monument to the Polish presence is still to be found. Other units in East Lothian included the Polish equivalent of the ATS (based at Kingsknowe) and a Polish Infantry and Motorised Cavalry School also based in North Berwick.

The 1st Polish Anti-Aircraft Regiment

A Polish 40mm Bofors Anti-Aircraft Battery of the 1st Polish Anti-Aircraft Regiment was based at RAF Drem. From approximately March 1942 this regiment became part of the 1st Polish Armoured Division and from 19th September 1942 the Regiment was based in Gullane with its HQ in the Marine Hotel, North Berwick. By this time the regiment had reached its full complement of 850 officers and men. From February to December 1943, a Cadet Officers’ School was based in Gullane.

1st Polish Armoured

Division Insignia.

1st Polish Armoured Division squadron (10th Mounted Rifles)

artwork with Division Formation sign, unit serial with

arm of service flash included.

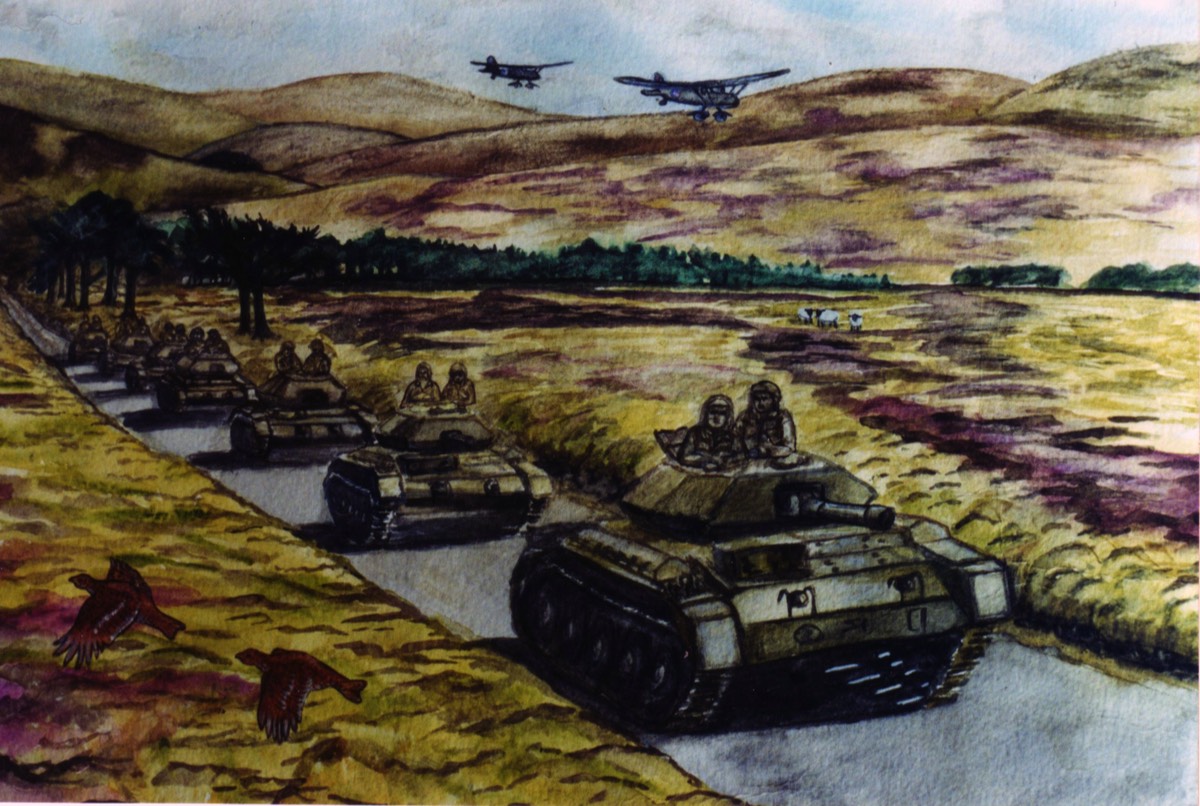

On exercise near Mayshiel above the future Whiteadder

Resevoir. Painted by Louise Nowell.

Training

During its time at Haddington the 10th Mounted Rifles was given extensive training; its instructors being sent on courses to English training centres and it also received more modem tanks. These were Covenanters and then Crusader Mk. III Cruiser tanks. Much of the regiment’s training took place on the gentle moorland of the Lammermuir Hills, an area that provided the vast space needed for tank manoeuvres and training in the techniques of mobile armoured warfare. The 10th Mounted Rifles was based in Amisfield Park, in Haddington. The photograph below shows its tanks emerging from between the Park’s two distinctive gateposts upon which are fixed two shields showing the Polish Eagle.

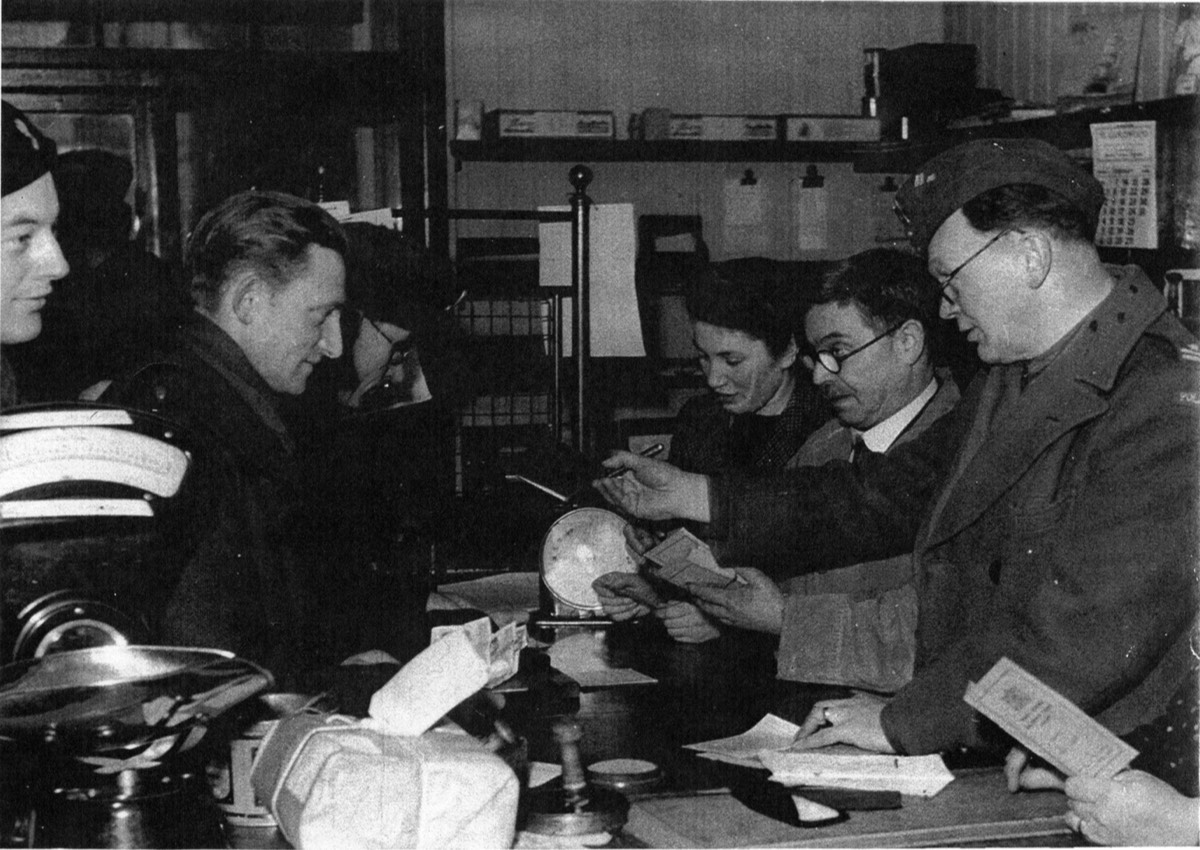

Polish troops in Gifford Post Office - Village Postmaster,

Willie Todd is 2nd from the right.

The soldier standing by the tank's barrel is Stanislaw Jesinski, father of Craig Statham (author of Lost East Lothian)

Leaving their base in Amisfield, Haddington. Note the Polish eagles on the gate pillars.

Memories Of The Poles In East Lothian

Mrs Mary Stenhouse, a schoolchild living in the valley now occupied by the Whiteadder Reservoir, recalls Polish tanks training in the vicinity:

“Polish soldiers tried to make tanks climb walls or dry-stane dykes. The devastation was unreal. As they came towards us the noise of the tank tracks on tarred roads could be heard miles away like thunder. They practised shelling on Mayshiel and Faseny and our father had sometimes to meet us from Kingside School as it was very frightening for two little girls.”

George Dixon, a young boy living below the Hopes Reservoir during the war, remembered being shelled by Polish gunners. He described how the Poles, who were supposed to be shelling in the Redstane Rig area, were overshooting by two miles and actually dropping shells into the Valley of the Hopes. He described how the shelling went on all morning before his father (the Water Board Attendant in the Hopes) was able to contact the Police who sent someone up to the range to stop it. Live ammunition and smoke shells were being used so it was fortunate that no one was injured. George remembers the Polish troops and the Police coming into the valley after this incident to search for unexploded shells that were then removed.

Mine Laying

Polish troops were responsible for laying many of the hundreds, if not thousands, of anti-personnel and anti-tank mines in the beach minefields along the coast of East Lothian. Unfortunately for those who had to dig them up after the war, the Poles failed to keep accurate maps of exactly where they lay and the job of digging them up was thus a dangerous one and did result in injuries for some of those involved.

The Scottish-Polish Society

Haddington had its own branch of the Scottish-Polish Society, a society created to foster good relations between local people and the Polish troops. Its President was Major G.H.M. Broun-Lindsay of Coulston. The Society used to hold meetings in the West Church Hall where lectures were given on topics such as “Poland’s western problem”, “Polish Christmas customs”, “Poland, her people and their country” and “Scots in Poland”. The society held choral evenings with both local and Polish choirs and musicians providing the entertainment and it held dances, for example in the Knox Institute, which helped maintain morale. The Society had over 140 members.

On 14th February 1943, at a large ceremony in Lady Kitty’s Garden, Haddington, Provost Alexander Aitchinson presented the C.O., 10th Mounted Rifles, with a Saltire flag and also a scroll bearing the signatures of the members of the Haddington branch of the Scottish-Polish Society to commemorate the unit’s time in Haddington. Haddington’s Home Guard unit supplied a Guard of Honour and some of the 10th Mounted Rifles’ tanks and Bren Gun Carriers were parked in the nearby Ball Alley. In reply the C.O. spoke saying:

“…nearly a year had passed since the Polish Mounted Rifles arrived in Haddington. [It was] the first Polish unit in East Lothian and he must frankly say that both sides were a little anxious as to how they would get on with each other. After a very short time, however, extremely friendly relations had been established owing to the Haddington people’s generous hospitality, friendship and full understanding of the Poles.”

In return the C.O. gave Provost Aitchinson a wall plaque, one that still hangs halfway up the staircase in Haddington’s Town House.

The Polish plaque mentioned above which is situated on the wall by the main stairwell in Haddington’s Town House.

The plaque reads: “To the people of Haddington from the 10th Mounted Rifles 1942.”

10th Mounted Rifles Leave Haddington

In May 1943 the regiment entrained at Haddington station and moved south to England. It later returned to Scotland but to Peebles this time and later to Dalkeith. The 10th Mounted Rifles was to land in Normandy in July 1944 and be heavily involved in the campaign to clear northern France, Belgium and Holland of their old enemy. The Division’s final act was the capture of Wilhelmshaven in May 1945.

10th Mounted Rifles loading their tanks onto flat cars in Haddington Station.

Polish Female Soldiers In East Lothian: A Film

A propaganda film unit visited Gullane in 1943 and filmed a female Polish unit marching to an inspection by a senior officer and while on manoeuvres along Gullane beach. The film gives rare and interesting views of the beach area and of the former Marine Hotel in Gullane. This was taken over after the war as a Fire Training School but it has now been converted into private flats. The film's content is firmly of the morale raising variety as it’s rather unlikely that the ladies would have gone to war in skirts and light shoes! Click on this link to see the film: Polish female soldiers. [Courtesy of Pathe News and You Tube. Thanks to Chris Holme]

Polish RAF Squadrons

A Polish night-fighter Squadron, No. 307 (City of Lwow), RAF, operated from Drem with Mosquito (NF VI) night fighter aircraft between November 1943 and March 1944. Its main task at the time was as a night intruder squadron flying over German airfields in Occupied France. Their nickname ‘Eagle Owls’ was thus an apt one.

307 Squadron Badge.

Let the experiences of the following Poles who, at one time or another, fought their enemy from the shores of East Lothian, stand as representatives of the many:

Sgt Sanetra seen here on the right standing by a Blenheim Mk IV at Turnhouse in 1942.

Sgt. Edward Sanetra

A.F.C. Test Pilot

Sergeant Edward Sanetra A.F.C. Test Pilot

Edward Sanetra’s story paralleled that of many other Poles who were to find their way to East Lothian. He joined the Polish Air Force in 1936 and thus faced the German invasion in 1939 when he and his comrades were unable to prevent their country falling to the combined German and Russian invasions. He was more fortunate than those who had to walk out of Poland to safety, as he was able to fly to Romania in one of the Polish Air Force’s last remaining aircraft. He made his way to the Black Sea, thence by Greek ship to Beirut and then Marseilles. Once in France he renewed his fight against the Germans and joined the French Air Force.

After France’s fall Edward was able to fly to Casablanca and gain passage aboard a British destroyer to England. There he joined his third Air Force when he became a member of 307 Squadron, flying Boulton Paul Defiants on night fighter patrols along the South Coast. A posting took him to Turnhouse and then to East Fortune and it was there he was to remain for most of the war. Edward Sanetra became a Test Pilot and remained in this dangerous occupation for four years. He survived three crashes including one that saw him crash into a field near Bolton.

Edward’s final posting was to Leuchars and, having attained the rank of Sergeant, he was demobbed in 1947. It’s not surprising, given this record, that he received the Air Force Cross and was mentioned in dispatches, as well as receiving a special honour from Poland.

Vladic Piekarski: Tank Commander

Vladic Piekarski was another example of a Pole who, after war service, ultimately settled in East Lothian. Ron’s story began as a frontier policeman, helping to guard the border in the Carpathian Mountains in the south of Poland, who, when the Germans marched in, walked out – all the way to the coast of Greece! There he was able to get aboard a ship and ultimately reach Glasgow.

Vladic joined the Polish Army in exile and came to Haddington with his tank regiment, the 10th Mounted Rifles. There he spent many months training in and around the town before moving south with his regiment, ultimately to land in Normandy and fight his way north east to the war’s end in Holland.

He once recounted an experience that vividly illustrated the bitterness towards the Nazis, which lay close to the surface of many Poles. Vladic witnessed surrendering SS troops emerging from their hiding places under the protection of a white flag only for them to explode concealed grenades among the Polish infantry who moved forward to take them prisoner. The Poles didn’t make the same mistake again!

After the war Vladic (now known locally as Ron Pye) settled in Haddington and married a local girl, Jean. He found work as a clock repairer but had to cycle all over East Lothian in search of such work. His endeavours brought their reward and he eventually came to own a jeweller’s business in the town. When the Berlin Wall came down and relations improved sufficiently between East and West, Vladic was able to visit Poland again and, some years after Jean had died, finally to return there to remarry and settle.

Wladyslaw Niedochodowicz: Second Lieutenant of Artillery

The following is quoted courtesy of the Scotland at War Trust, the website of which includes a section where this officer refers to his time at Gosford House. It was written by Wladyslaw’s daughter, Marta Nordstrom Bagot, and gives fleeting glimpses of what service in a foreign country must have been like for the Poles.

http://www.scotsatwar.co.uk/veteransreminiscences/Niedochodowicz.htm

Around this time the Regiment was given new heavy armour, vehicles and guns, and in the meantime the soldiers and townsfolk began to get along more and more. A Polish-Scottish Association was started in Edinburgh as well as a British-Polish Association in Bradford, England. Both these associations were active in organising free time for the soldiers and even vacations together with English families.

At the end of 1942 my father went for his first two weeks’ vacation to stay with the Bairstow family in Bradford. The head of the family was a coal merchant and they lived in a nice cottage in a suburb of the city. Christmas and New Year was a time for family traditions and drinking beer in their local public house. But the biggest impression made on my father was drinking huge amounts of tea with milk during these days.

Another thing new to him was the language. Learning and using phrases daily such as ‘how do you do’, greeting people in the morning and wishing them a ‘nice day’ even though it was raining outside, and using the words ‘sweet home’ (which seemed to be a symbol for the English way of life: closed, discreet and intimate), was often really amusing for him.

12 June 1943 saw the beginning of the great march of troops through north and middle England towards Wales, to a place near Brecon, Hereford called Abergavenny, and afterwards through the middle of England to Brandon, in the Cambridge district. After some days at the new camp rumours began circulating about concentrations of troops in preparation for an invasion of the continent.

At the end of October 1943, the Regiment returned to Gosford House in Scotland, and General Montgomery, the Commander-in-Chief, gave orders for short vacations only.

My father and a friend took a short trip in November down to London. They stayed at a Bed & Breakfast in Bedford Way, the owner of which was Swiss. The bombing of London was still continuing almost each night, starting at about 8pm and not stopping until about 2 to 3am. My father writes about the English peoples’ courage and discipline, which he admired during those days.

January 1944 — The 1st Polish Armoured Division is put with the 21st Army Group under the command of General Montgomery. February 1944 — All permission for vacations was suspended and the word ‘readiness’ became the whisper within the Division. The group received new tanks for their use.”

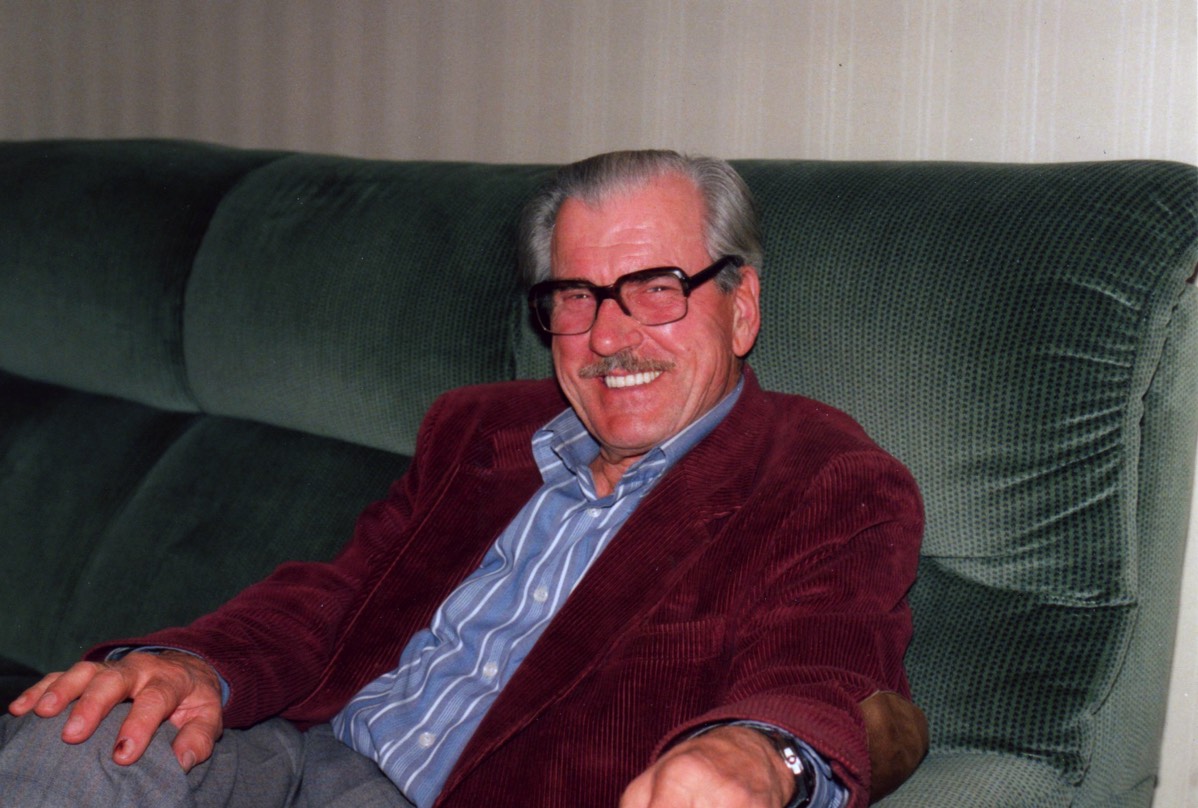

General Maczek

Stanlislaw Maczek had been born in Eastern Poland on 31st March 1892 and after joining the pre-war Polish army, had risen to command the 10th Mechanised Cavalry Brigade at the time of the German invasion. His unit was ordered to move into Hungary to escape encirclement by the Russians and Germans. Internment there didn’t prevent the men escaping to France.

In Paris Maczek was awarded the Virtuti Militari, the highest Polish military decoration, and raised to the rank of Major General. Germany’s success in France forced General Maczek to embark on a long and arduous escape, one that took him through France, across the Mediterranean to Algeria and Morocco and back to Portugal before he was able to reach the UK. General Maczek was then appointed Commander of the 1st Polish Armoured Division, which, of course, saw him posted to East Lothian.

Like many of his former comrades, General Stanislaw Maczek chose to remain in Scotland after the war. Poland was then under Soviet control and many former soldiers who had fought for the Allies were being very badly treated. To return home was, simply, dangerous. Despite his role in the Allied Forces and his former high rank in the Polish Army, Maczek could not be awarded a pension from the British Authorities. He was forced to look for low paid jobs (such as working in a shop in Gifford) just to make ends meet and, at one stage, was employed by one of his former subordinates. It took a Press campaign instigated by John Steinberger, a former tank driver, who recognized General Maczek in the shop in Gifford, to reverse this injustice.

General Maczek’s wartime exertions did nothing to shorten his long and interesting life. He died on the 10th December 1994, aged 102!

Lance Corporal Tadeusz Brylak, 1st Polish Mounted Artillery Regiment

To read Tadeusz’s fascinating personal story click here.